This week’s readings were informative, but several seemed slightly outdated. Such is the nature of the technology beast I suppose. Just as we begin to discover, think about, write about, reflect upon, and understand some new technology or technological context, something changes. I can’t imagine it’s really even possible for a book (a textbook in particular) to keep up with the constant changes occurring seemingly overnight.

This week’s readings were informative, but several seemed slightly outdated. Such is the nature of the technology beast I suppose. Just as we begin to discover, think about, write about, reflect upon, and understand some new technology or technological context, something changes. I can’t imagine it’s really even possible for a book (a textbook in particular) to keep up with the constant changes occurring seemingly overnight.Many of the assertions proffered in the Moran article “linked” me back to a book I read last summer, entitled The Dumbest Generation or Don’t Trust Anyone Under Thirty. www.dumbestgenerationwww.thedumbestgeneration.com This book, written by a Cambridge Scholar, presents a thorough and seemingly well supported discussion about our students and their use of technology. The primary argument presented in the book is that despite our (relatively successful – at least in my experience) intentions and efforts to make access to technology equally available to all students, our students have failed to do their part and use the technology made available to research, and expand and enrich, their knowledge bases. Instead, the author purports, our students have done quite the opposite and are using the technology to “cocoon” themselves into tight little social networks, building virtual walls that shield them from and blind them to the world in which they live. Moran argues that if we are to assume that “technology improves student learning,” then assuring access and teaching students how to use it are our goals as educators. So, here we are years later, and I think it’s pretty safe to say we’ve spent tons and tons of money, but are seeing little return on our investment, at least in terms of academic gains. That leads me to ask myself why my students who are by most standards technologically literate, don’t know what key terms to type into the google search bar if trying to locate a professional organization on their field. Or, why they don’t know what “evaluate the credibility” of a site means, or why they don’t know what Publisher is, or how to safely save their work for efficient retrieval. They think grammar/spell check is the bottom line, end all to be all god of writing correctness, despite the fact that it is highly flawed, has a vocabulary equivalent to that of an 8th grader ( I read that in an article I cannot locate - ugh!), and is not familiar with the specialized vocabulary of their Career and Technical areas of specialty. I could go on (of course! LOL!), but.... So, now I’m compelled to think that WE, teachers, have failed somewhere (jump on the bandwagon, right?). On page 207 Moran tells us that whether we like it or not, it’s our job to read the research, learn the technology, and TEACH our students how to use it for (I’m guessing here) academic purposes and not simply social networking. I teach 10th and 12 graders, and I mourn the fact that I must teach otherwise techno-savvy students how to perform basic word processing functions each year before we can even begin typing papers. These students are on Facebook, have ipods, and all kinds of other techno-tools, but are simply not accustomed to using them for academic pursuits. Maybe it’s not the actual teachers, but the archaic rules and policies in some of our schools, forbidding and making impossible the use of email in/from school, or blocking most of the sites that would be “hits” during a research query. I actually had to ask to have Purdue Owl unblocked this year so my students could use it as an MLA resource. How can I fault them for not knowing and understanding how to read and navigate the site, spending two periods showing them how, if they can’t access it from school? As much as Moran cites wealth (or lack of) as an issue for accessibility, I contend we have a more serious problem with administrators who are uninformed and fearful, and teachers of the same, who refuse to allow technology into their classrooms and to teach students how to use school/academic technology for its intended purpose – to enlighten and enrich the learner and learning process!

I appreciated the Diana George article for the simple fact that I have tried a multi-modal project in Writing and Rhetoric class before, and she definitely offered some insight into how I can work on improving that project and why I would want to. I also thought she made an important statement about the role of the teacher, charging us to help students be critical, as well as enthusiastic, consumers of the newer forms of “text.” I found the historical perspectives helpful, but they made ME feel outdated, as I recall writing papers about these evolving issues and trends in the field way back during undergrad (eeeeks!!).

Miller and Shepherd provided a very interesting history of the evolution of the blog as a genre. I was repeatedly surprised during my reading of this (and other previous articles) that the authors didn’t reference Deborah Dean. She authored Genre Theory a few years ago (published by NCTE) www.nwp.org/cs/public/print/resource/2988 .Much of the discussion in the article was mirrored in Dean’s book, but was presented in a teacher –friendly format. That book revolutionized my understanding of the term genre. I also liked the section on Kairos, an idea I never did quite grasp during undergrad. The examples Miller and Shepherd provided served to make its meaning slightly more clear for me. I also loved that they shared the website for Kairos. One of my undergrad professors frequently shared this site with us, and I had completely forgotten about it until this article. I definitely plan to check it out and see what I can glean. The sections on ancestral genres and etymology were also interesting. I ‘m not quite a history buff (although I do find it useful and fun to know), but I AM a journaler. I was unable to decide if I agreed with Elbow or Mallon in regards to the differences/similarities between diaries and journals.

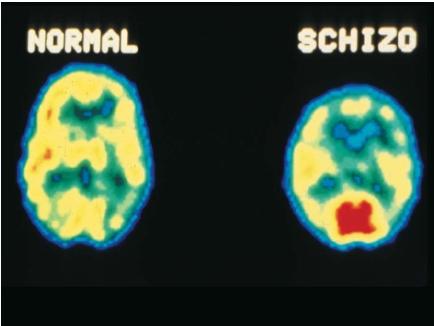

The common thread I found I all the articles this week was the fact that, as teachers, we must constantly change too. Change is often good, but too much at once, without thorough reading of the research, some writing and reflection, could result in a definite case of "Enforced Educational Schizophrenia" as we endeavor to occupy all our roles well and do the very best we can for each of our uniquely situated students.